Using the characters of Ezra Jennings, from The Moonstone, and Sherlock Holmes as my focus, I would like to explore three related themes in this essay. First of all, I’ll discuss Drugs and Drug-Users in 19th century literature. As we all know, of course, Ezra Jennings is a notable opium addict, and Holmes a user of cocaine, morphine, and strong tobacco. After briefly dealing with the importance of drugs, I will broaden the scope and examine Jennings and Holmes as detectives and men of science, comparing and contrasting the two characters. Finally, this will bring us onto the topic of reason, logic, intuition, and the unconscious, with some further comments relating the two characters and the fiction they appear in to psychoanalysis.

DRUGS AND DRUG USERS IN NINETEENTH CENTURY FICTION

First of all, I’d like to consider the case of opium, which is so central to the plot of The Moonstone. This narcotic, a derivative of the opium poppy, has quite a literary pedigree, with a central text being Thomas De Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium Eater, which Ezra Jennings cites as an authority on the drug. Its use at the beginning of the nineteenth century as a pharmaceutical treatment, indeed, a panacea for all sorts of medical conditions, was widespread throughout British society. It had become increasingly easily available due to massive cultivation of the opium poppy in British India, and was sold in the form of pills, powders, and patent medicines, for everything from gout, to rheumatism, respiratory illness, and to stop babies crying. It was most common in the form that De Quincey and Ezra Jennings take it, as a tincture of opium in alcohol, called laudanum. De Quincey discusses his initial use of opium, and subsequent addiction to it, like that of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, as the result of its use for medicinal purposes, as is the case with Ezra Jennings. He then deals with the Pleasures of Opium and the Pains of Opium, in which he dwells more closely on the psychotropic effects of opium on the intellect, on the perceptions, and on the dreams or visions that can result from its use. Clearly though, in Ezra Jennings, we have a character who uses opium as an anaesthetic, and not for recreation. However, as the availability of opium became more restricted in Britain, through the 1868 Pharmacy Act, for example, the perception of opium was changing. The opium eater who uses say laudanum primarily to treat illness, gives way to the opium smoker, a dangerous degenerate.

It’s interesting to note that the British opium trade with China and the two Opium Wars of the middle of the 19th century are what led to the massive rise in opium addiction in China. Along with the spread of the Chinese diaspora in the West, this is what gives us, at the end of the 19th c., the image of the opium den as the site of Eastern decadence and vice that we get, for example, in the Sherlock Holmes story “The Man with the Twisted Lip” (from The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes), where Watson descends into “the long, low room, thick and heavy with the brown opium smoke,” through which one could “dimly catch a glimpse of bodies lying in strange fantastic poses, bowed shoulders, bent knees, heads thrown back”, and where he is offered a pipe by a Malay attendant. The move of the site of opium use, from the cosy living room that De Quincey describes, with the roaring fire and the tea ready, to this den of vice, is perhaps another example of the legacy of the Oriental Other returning from the colonies to trouble the very heart of the Empire, as we so often see in Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories. We could relate this to Wilkie Collins’s contrasting depictions of the opium eater, Jennings, who must choose between the pain of his disease and the horror of opium dreams, and his inclusion of opium smoking in the list of Colonel Herncastle’s vices, the returning colonial who also indulges in chemical experiments, collecting old books, and carousing in slums in his “solitary, vicious, underground life”(44). It’s interesting to note that Watson attributes Isa Whitney’s opium use, in “The Man with the Twisted Lip”, to “some foolish freak when he was at college; for having read De Quincey’s description of his dreams and sensations, he had drenched his tobacco with laudanum in an attempt to produce the same effects.”

In literary terms, however, we can also see, beginning with De Quincey, a rise in the myth of opium use, indeed use of any psychotropic drug, as a way of accessing the unconscious, as an aid to creativity, for its “vertus onéiropompes”, as Patrick Waldberg calls them in his introduction to Arnould de Liedekerke’s La Belle Époque de l’Opium. De Liedekerke goes on to tell us that :

“avec Quincey, la drogue sortait du cadre strictement médicinal pour devenir une attitude esthétique et morale, voire un engagement. Elle se présentait désormais sous sa forme moderne, « romantique », à la façon d’un élixir séduisant et dangereux, comme une porte ouverte sur le rêve et l’imaginaire.”(60)

[“with De Quincey, the drug came out of the strictly medical framework to become a whole moral and aesthetic pose, even a radical engagement. It appeared, then, under its modern form, “Romantic”, a seductive elixir, a dangerous open door to Dream and Imagination” – my translation]

This tendency would pass very strongly into French literature through Baudalaire’s essays in Les paradis artificiels, for example, which include a detailed commentary on De Quincey’s work. The link between the figure of the decadent and drug use, particularly opium, remains strong also in English literature, with Wilde’s Dorian Gray taking refuge in an opium den in an attempt to “buy oblivion”.

Turning to the example of Sherlock Holmes, we see that the scientific advances which have replaced the use of opium in medicine with that of morphine, as an anaesthetic, and the new development of cocaine, have not passed him by. But Holmes is not a user of morphine and cocaine for medicinal purposes; indeed we might categorise him rather with those who De Quincey tells us turn to drugs for “the general purpose of seeking relief from ennui, or tædium vitae.” (227) At the beginning of The Sign of Four, we are given a detailed description of Holmes injecting himself with the famous “seven-per-cent solution” of cocaine, as follows:

Sherlock Holmes took his bottle from the corner of the mantelpiece, and his hypodermic syringe from its neat morocco case. With his long, white, nervous fingers, he adjusted the delicate needle and rolled back his sinewy forearm and wrist, all dotted and scarred with innumerable puncture-marks. Finally, he thrust the sharp point home, pressed down the tiny piston, and sank back into the velvet-lined armchair with a long sigh of satisfaction.

While Watson at this point finally decides to remonstrate with Holmes, in strong terms, against his habitual use of the drug, Holmes argues that he finds it

“so transcendentally stimulating and clarifying to the mind that its secondary action is a matter of small moment.” He goes on to explain that “my mind… rebels at stagnation. Give me problems, give me work, give me the most abstruse cryptogram, or the most intricate analysis, and I am in my own proper atmosphere. I can dispense then with artificial stimulants. But I abhor the dull routine of existence. I crave for mental exaltation.”

For Holmes, then, the use of cocaine, or morphine, with which he alternates it, is a remedy only to “the dull routine of existence”, a remedy which is also provided by his work. It is also perhaps a substitute for, or a suppressant of, normal human desires. At the end of The Sign of Four, when Watson comments on the unfairness of Holmes having no reward, while he himself has got a wife from the affair, and Jones of Scotland Yard has received the credit, Holmes says “For me, there still remains the cocaine bottle”.

Further references to Holmes’s use of cocaine and morphine become sparser in the later stories, with Watson referring in passing to cocaine as Holmes’s only vice. Indeed, in “The Adventure of the Missing Three-Quarter”, in The Return of Sherlock Holmes, Watson declares that “for years I had gradually weaned him from that drug mania which had threatened once to check his remarkable career. Now I knew that under ordinary circumstances he no longer craved for that artificial stimulus, but I was well aware that the fiend was not dead but sleeping”. This shows remarkable insight on Conan Doyle’s part, considering that the understanding of drug abuse and addiction was only very partial when he wrote this. Indeed, Sigmund Freud, at the beginning of his career, wrote very positively of his own use of cocaine (but we’ll come back to him later).

For Ezra Jennings, the only positive side to his own opium use is the relief of his terminal medical condition, as he says (380) “to that all-potent, all-merciful drug, I am indebted for a respite of many years from my sentence of death”. However, he has to then deal with the penalty of abuse of the drug: “My nervous system is shattered; my nights are nights of horror.” But his own opium use is almost incidental to the part that opium goes on to play in the plot of The Moonstone, when he conducts his experiment attempting to recreate Franklin Blake’s movements on the night of the theft of the jewel. The ability to act unconsciously while under the influence of the drug was something that Collins of course had personal experience of, as he had become an habitual user of opium to treat his own rheumatic gout.

Towards the end of his life, he apparently consumed enough opium daily to kill several people, and claimed to have composed entire passages of The Moonstone while under the influence of so much laudanum that he could not recall having written them. The situation is one of “Chinese-box intricacy” as Alethea Hayter calls it in her book Opium and the Romantic Imagination: “an opium-induced re-enactment of an opium-induced action, set up by an opium-dependent doctor who uncovers the mystery of the crime”, and all this written by an author under the influence of a heavy dose of opium himself.

Thus we have Ezra Jennings, who uses opium as a medical treatment, and in an experiment that proclaims itself to be medical and scientific in nature, and Sherlock Holmes, a recreational drug user and addict, who rather falls into the tradition of the drug-using decadent, or perhaps the voyant whose duty, as Rimbaud tells us, is to engage in “un long, immense et raisonné dérèglement de tous les sens.” Which sounds like just the sort of experiment that Holmes would enthusiastically participate in.

THE SCIENCE OF DEDUCTION AND THE ART OF MEDICINE

This brings us on to the second main thrust of our argument, in which I’d like to consider Holmes and Jennings more generally as characters, as detectives, and as men of science.

Both Holmes and Jennings are adamant in their consideration of themselves as scientists, indeed we can draw several parallels between the two here. They are both authors of scientific treatises. Jennings has been working for years on “a book on the intricate and delicate subject of the brain and the nervous system” (374), and Holmes is the author of monographs on subjects as diverse as the identification of 140 different types of cigar-ash, on ciphers, on the distinctiveness of the human ear, or the Polyphonic Motets of Lassus (whatever those may be).

[Note : years later, I found out : I went to visit the Sherlock Holmes Apartment at 221b Baker Street, in London ; this wonderful place is often occupired by an actor playing Holmes ; the day I was there, it was an elderly, out-of-work actor, who seemed wonderful and Shakespearean. The monographs of Holmes are all present. I asked “Holmes”, and he told me what a polyphonic motet is and who indeed Lasses was. I then asked him, having seen the “Tantalus”, a drinks tray that locks to stop the servants getting at it, “where he kept the 7% solutuion of Cocaine?” ; he looked at me slyly out of the corner of his eye : “Ah, a connoisseur, I see!” And then he took from a secret compartment, a Morocco-Leather case, in which there was a vial of the solution, and a syringe …. Needless to say, my Heart was Full. Later, he caught my eye, and winked, and said “Just popping out for a spot of lunch” … His rheumy eye, and his unsteady gait told me that it would be mainly Liquid. I blessed him, and wished him, silently, a John Lewis ad voiceover. May he “rest” in peace, and never again be “out of work”].

AHEM.

They both position themselves within the tradition of scientific knowledge, and claim that their work in figuring out the truth, in their roles as detectives, is based on experiment, on deduction, and on solid research.

Ezra Jennings is a doctor, and he calls on the support of the work of previous experts in his suggestion of the opium experiment to Franklin Blake. As he says (390), “Science sanctions my proposal, as fanciful as it may seem”. He quotes the authority of Dr Carpenter and of Dr Elliotson, for his theory of what will happen if they proceed with the experiment, for the “physiological principle” on which he is acting, and for the theory of state-dependent memory which he hopes will be borne out by events. Indeed, Collins himself claims, in his preface, that he has “ascertained, not only from books, but from living authorities as well, what the result of that experiment would really have been.”(3)

Jennings’s description of how he went about filling in the blanks in Mr Candy’s delirious ramblings, though he claims its scientific basis, may remind us less of standard medical practice than of Sherlock Holmes and his science of deduction. He says: “I treated the result thus obtained, on something like the principle which one adopts in putting together a child’s “puzzle”. It is all confusion to begin with; but it may be all brought into order and shape, if you can only find the right way.”(374)

Holmes elaborates his “Science of Deduction”, as he calls it, throughout Conan Doyle’s stories, and maintains that his is a true, empirical science. In A Study in Scarlet, we see Watson reading an article that turns out to have been written by Holmes called “The Book of Life”, in which he claims that the Science of Deduction and Analysis is one that renders deceit impossible, whose conclusions are as infallible as so many proposition of Euclid. He claims in it “that all life is a great chain, the nature of which is known whenever we are shown a single link of it”.

We might be tempted to agree with Watson’s initial impression of these claims as “ineffable twaddle!”, so far-fetched do the conclusions seem. As we might perhaps tend to support the view of the lawyer Mr Bruff, when he dismisses Ezra Jenning’s opium experiment as “a piece of trickery, akin to the trickery of mesmerism, clairvoyance and the like”(402). And though Watson, time after time, is convinced that what had seemed to be a supernatural feat of clairvoyant insight on Holmes’s part was in fact a perfectly simple, logical piece of reasoning, just as Bruff and Betteredge, the sceptics, are completely convinced by Jennings’s experiment, we as readers must remain somewhat sceptical. I’ll discuss the status of reason and logic in their detective work a little later, but first I want to draw your attention to the tension within the authors’ presentations of these two characters that would lead us to have doubts about their status as scientists.

Many critics have remarked on the usefulness of analysing Holmes as a doctor. There’s a particularly good treatment of this idea in Dominique Meyer-Bolzinger’s Une méthode clinique dans l’enquête policière, where the author discusses the medical links in the creation of Holmes as a character, and then wonders what kind of doctor we might consider him. I don’t have time to go into very much detail on this, but I can recommend the book. Briefly, Holmes was created by Conan Doyle, who was a qualified doctor, and who perhaps based his creation on the brilliant Dr Joseph Bell, with whom he had studied in Edinburgh. Doctors like Bell, and another possibility that Meyer-Bolzinger mentions, Charcot, were famous for their at-a-glance diagnoses of patients, and indeed Holmes is presented in many ways like a doctor. He is first encountered in A Study in Scarlet by Watson carrying out experiments in the dissecting-rooms of a hospital, beating the bodies with a stick to study post-mortem bruising, and we often see him involved in intricate chemical experiments. Though he is never called a doctor, he does refer to himself as a “consulting” detective, and his rooms in Baker Street have something of the doctor’s surgery about them, a place where people come for a diagnosis of their problems. He even refers to Dr Watson as his “colleague” on several occasions, and is an expert in certain very specific medical areas. But there is more to it than that. As Meyer-Bolzinger points out, if Holmes has a speciality, it is difficult to pin down, possibly experimental science, perhaps logic, criminology, or the yet-to-be-invented forensic science.

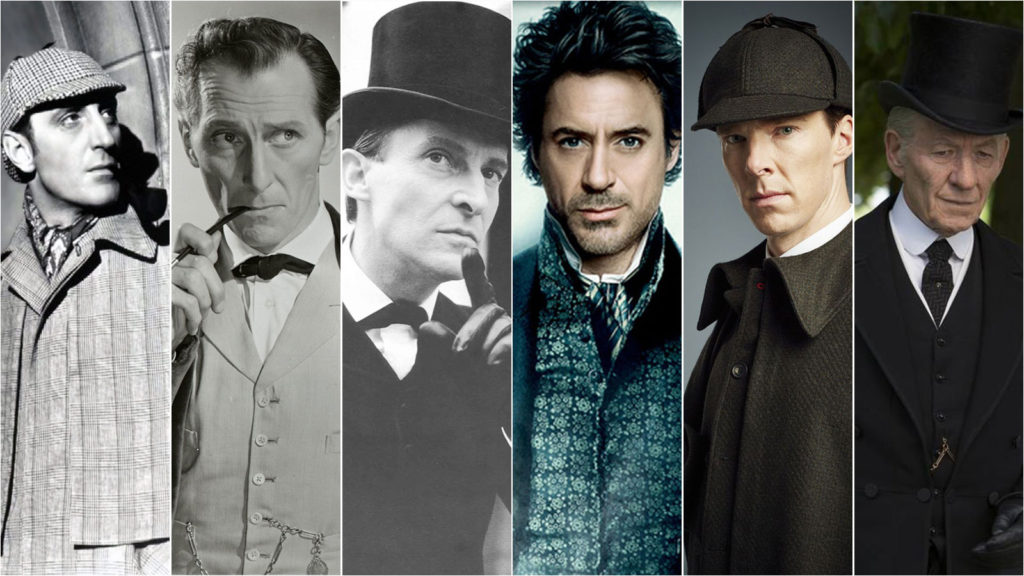

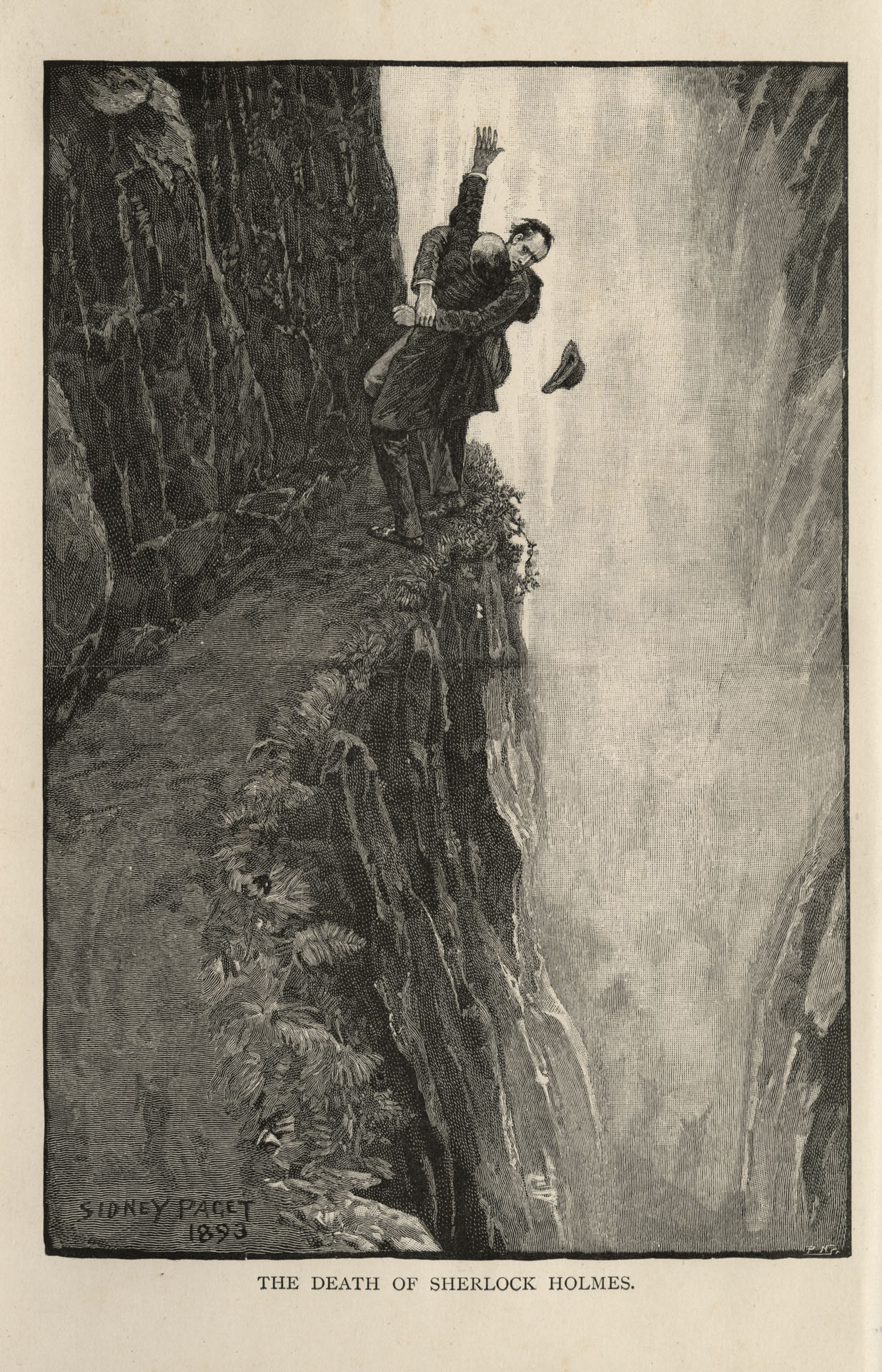

However, Holmes often appears to have powers that border on the supernatural, seeing the unseen, discovering the hidden, even telepathically reading Watson’s thoughts on several occasions. If he explains to us afterwards how he did it, there is still a doubt in our minds, a suspicion that there is more to it than we understand. Holmes himself is very partial to the dramatic reveal at the end of his cases, as when he makes the Mazarin Stone appear in the pocket of Lord Cantlemere, and his guessing of clients professions, origins, and concerns, or his full description of the previous owner of Watson’s pocket watch merely from holding it are highly reminiscent of the tricks of a conjuror or stage-magician. In some of his exploits, we might be tempted to read not the tricks of a fraud, but the miraculous exploits of a sorcerer or miracle worker, as in “The Adventure of the Blanched Soldier”, when he effectively “cures” a case of leprosy, or in his apparent return from the dead, after he was supposed to have plunged off the Reichenbach Falls with Professor Moriarty in “The Final Problem”.

Conan Doyle’s portrayal of Holmes maintains this tension between Holmes as man of science, and Holmes as man of mystery. His experiments in obscure chemistry and knowledge of poisons are reminiscent of the work of an alchemist, and Holmes’s retreat into the trance-like state in which he meditates on his problems, like in “The

Adventure of the Man with the Twisted Lip”, where he reclines on cushions and surrounds himself with tobacco-smoke, seem more like the actions of a seer or clairvoyant than those of a scientist. No matter how much Holmes himself insists on everything being logic and deduction, the very presence in the stories of possibly supernatural elements, and the depiction of Holmes as a mystic, raises this possibility with the reader. The Hound of the Baskervilles and the Sussex Vampire may be explained at the end as nothing supernatural, but there is no denying the presence of the supernatural and the fantastic in the narratives, and of Holmes as a character halfway between the scientist and the dabbler in the occult.

In the character of Ezra Jennings we can see the same tension at work. He may present himself as a doctor, and a man of science, but the portrayal of him by Collins leads us to associate him with more esoteric sources of knowledge. Consider his appearance, which so strikes Franklin Blake, with his “piebald hair” and his appearance of youth and age at the same time, his “gipsy complexion” and his nose which “presented the fine shape and modelling so often found among the ancient peoples of the East, so seldom visible among the newer races of the West.” (326) and his “eyes dreamy and mournful, and deeply sunk in their orbits” which “took your attention at their will”. There is a strong connection here with the mysterious and the occult, with ancient Eastern knowledge, gipsy magic, hypnotically powerful eyes. Jennings does not strike us as a sober man of science, but as a strange prophetic figure, an outcast from society. The distrust of the neighbours stemming from his appearance is understandable: he seems the type that in former times would have been driven off as a witch or sorcerer, and blamed for giving people the evil eye. He also admits himself, to being a man born with a “female constitution”, which may remind us of other mystical, prophet figures such as Tiresias, or shamans in some primitive societies who display both male and female characteristics.

Carmina et Errores https://saxonides.wordpress.com/2015/09/21/antigone/

In fact, Jennings seems less like the doctor, and figure representing positivistic, empirical science, than a refugee from a Gothic novel. His appearance suggests the exotic, mysterious Eastern magician, or wandering gipsy, his tragic and mysterious past, loss of the ones he loved, and persecution by society, his suffering from an unnamed disease and from the hellish visions visited on him by his opium addiction, even his melodramatic and emotional responses to his dealings with Franklin Blake and Rachel Verinder, all seem to make him a sort of cursed exile figure, perhaps comparable to Maturin’s Melmoth the Wanderer, more typical of the earlier Gothic novel, even though here he also functions as both scientist and perhaps the most effective detective in the novel. Here we can see the direct line from the Gothic Novel, to the Sensation novel, and on to the Detective Novel, and it’s useful to realise that there is no clear line of demarcation between these genres, but in fact a shared lineage within a series of overlapping classifications.

Despite the strong association of Ezra Jennings with a supernatural sorcerer type, this comes more from his appearance than his actions. Indeed, he is portrayed as a benevolent, very human, humble character, who misses his loved ones, and has a “yearning for a little human sympathy”. His isolation is not by choice, and he bears it with great pain. Compare this to Sherlock Holmes, who has chosen an almost complete isolation from ordinary human society. We have the impression that his friendship with Watson is the one true link he has to another human being, and that otherwise he holds himself aloof, displaying an almost autistic lack of desire, at times, for conventional life, and conventional relationships. Watson compares him to a cold calculating machine, and, when he springs into action, he is often also referred to in animal terms, springing like a tiger, or going at a trail like a bloodhound. Indeed, if Ezra Jennings can be associated by his distinctive, unalterable appearance with the figure of the magician, then Holmes by his very ability to change his appearance might also be again compared to some kind of protean, shape-shifting wizard. His transformation into various characters is so convincing that Watson himself is often fooled. Holmes may explain that it is all posture, makeup and acting, but there is still something disturbingly magical in his adopting of different personae.

REASON, LOGIC, INTUITION, AND THE UNCONSCIOUS

Moving on to consider the status of scientific knowledge and reason in these narratives, it’s useful to refer to Carlo Ginzburg’s seminal essay “Clues: Roots of a Scientific Paradigm”. The essay has been published in several versions, and the one I refer to is the English translation equivalent to the French “Traces: racines d’un paradigme indiciaire”, which appears in the collection Mythes, Emblèmes, Traces. Morphologie et histoire. Here, Ginzburg draws the connections between Morelli, an Italian art critic whose attributions of works of art focussed on small, inimitable details, such as the way folds of cloth were painted, or ears, or fingers, the work of Sigmund Freud, and the detective methods of Sherlock Holmes. It would be impossible to give a full account here of the work, but Ginzburg traces a parallel between the three methods, those of Morelli, Freud, and Holmes, as “In all three cases tiny details provide the key to a deeper reality, inaccessible by other methods. These details may be symptoms, for Freud, or clues, for Holmes, or features of paintings, for Morelli”. He explains this triple analogy thus :

There is an obvious answer. Freud was a doctor; Morelli had a degree in medicine; Conan Doyle had been a doctor before settling down to write. In all three cases we can invoke the model of medical semiotics or symptomatology-the discipline which permits diagnosis, though the disease cannot be directly observed, on the basis of superficial symptoms or signs, often irrelevant to the eye of the layman, or even of Dr. Watson….Toward the end of the nineteenth century (more precisely, the decade 1870-1880), this “semiotic” approach, a paradigm or model based on the interpretation of clues, had become increasingly influential in the field of human sciences.

He contrasts this semiotic, diagnostic approach, which he calls “divinatory”, with the anatomical, naturalistic approach that had been more prevalent in scientific method since Galileo, where evidence and experiment lead to empirical conclusions, rather than signs and clues leading to conjectural leaps.

For the purposes of this presentation, we can place Holmes and Ezra Jennings squarely within the diagnostic, semiotic paradigm, where the gaps in knowledge are filled in, as in Jennings’s reconstruction of Mr Candy’s ramblings, by leaps of intuition rather than solid proof. The work of the detective was, in these early

detective fictions, not as solidly logical as the detectives themselves would have us believe.

Indeed, if we look at Sherlock Holmes’s so-called “Science of Deduction”, we can see that in fact he is not actually using deduction at all, in a strictly logical sense. Neither is he using induction. As has been pointed out by Umberto Eco and Thomas Sebeok in The Sign of Three: Dupin, Holmes, Peirce, Holmes uses something closer to what the American logician Charles Sanders Peirce calls “abduction”. Deduction is what Peirce calls a necessary inference, and induction a probable inference, whereas abduction exists somewhere in between the two. It is more like a type of conjecture, or educated guess, based on hints.

(a brief illustration of this will help understand what the argument is:

If we think in terms of syllogistic argument, (a=b, b=c, 🡪 a=c) then :

Deduction is argument from population to random sample. General 🡪 specific.

So if all the balls in a jar are red, and all the balls in this sample are from the jar, then all the balls in the sample are red.

Induction is argument from sample to population. Specific 🡪 general.

If all the balls in this sample are red, and all the balls in the sample are from the jar, then all the balls in the jar are red. X problem.

Abduction is conclusion based on the sample. Making a probable hypothesis.

All the balls in the jar are red, all the balls in the sample are red, then all the balls in the sample are from the jar.)

We can see that this is more similar to the way that Holmes infers facts about his clients. For example, in “The Greek Interpreter” (Memoirs), when Holmes and his brother Mycroft are competing to come to conclusions about a man based purely on his appearance, they state that he is an old soldier, recently discharged, and a non-commissioned officer, who served in India. Their clues that suggest these conclusions are the man’s military bearing, his expression of authority, and his sun-baked skin. Now of course they are probably correct, particularly given the context of a London gentlemen’s club, but it would be ridiculous to suggest that the only possible reason for a man having an expression of authority and sun-baked skin would be the one they give, and therefore what they call deductions are not necessary conclusions, but rather very insightful guesses, based on observation of small details that might be ignored by most people. When Holmes says in his article in A Study in Scarlet, that “By a man’s finger-nails, by his coat-sleeve, by his boots, by his trouser knees, by the callosities of his forefinger and thumb, by his expression, by his shirt-cuffs – by each of these things a man’s calling is plainly revealed”, we may amend that to plainly suggested, but not proven. The parallel with Morelli’s method of attributing works of art is plain, but the parallel with Freud is perhaps a little more problematic. For Holmes can often be proved right or wrong, and his observations, while not logically foolproof, are acute and almost invariably correct. With Freud, his diagnosis of neuroses based on small, unnoticed things such as a patient’s choice of language, slips of the tongue, or physical symptoms also rely on our accepting his

whole theory of the unconscious. His solutions are unverifiable, and as such cannot be disproved either.

However, while we may or may not believe in Freud’s theories, there is no doubt that they provide a useful system for analysing fiction. As Freud was developing what would be become psychoanalysis, in the late nineteenth century, it is interesting to trace the parallel working out of similar concerns in fiction. While Freud makes claims for his conjectural, diagnostic methods as firmly scientific, we see Ezra Jennings as a doctor, and Holmes as a detective, doing the same thing, within the same context of the rise of this semiotic paradigm, as Ginzburg demonstrates, at that period in history. We have previously discussed how we can usefully propose a Freudian reading of The Moonstone, particularly in relation to the sexual symbolism of the theft of the stone, and, as we saw in Jonathan’s presentation, the Shivering Sands as a site for an encounter between Franklin Blake and Rosanna Spearman. We’ve also discussed the resurgence of danger with its origins in the Colonies in both The Moonstone and the Holmes stories as a “return of the repressed”, and the presence of the Uncanny in both these sets of narratives.

The parallel that I would like to draw is between the detective work that Ezra Jennings undertakes and psychoanalysis. When he attempts to reconstruct the thread of Mr Candy’s delirious ramblings, we can recall (374) that it was in the context of his own work on “the intricate and delicate subject of the brain and the nervous system”. He notes down the seemingly disconnected “wanderings” of the patient, and then he approaches it like a puzzle. He says:

Acting on this plan, I filled in each blank space on the paper, with what the words or phrases on either side of it suggested to me as the speaker’s meaning; altering over and over again, until my additions followed naturally on the spoken words which came before them, and fitted naturally into the spoken words which came after them. The result was, that I not only occupied in this way many vacant and anxious hours, but that I arrived at something which was (it seemed to me) a confirmation of the theory that I held. (375)

Jennings is using the same type of reasoning here that Holmes uses, making educated guesses that fit the surrounding circumstances. But, like Freud, he is taking the words that a patient speaks, seemingly disconnectedly, and filling in the gaps, with what those words suggest to him, and, not incidentally, by providing the material of association himself, confirming his theory to himself.

We can also look at the opium experiment through the lens of psychoanalysis. What Jennings is attempting to prove, is that under the influence of opium, Franklin Blake has unconsciously acted upon the concerns that were uppermost in his conscious mind, by reproducing the exact circumstances that led to the previous act. The insistence here on the unconscious is of course reminiscent of Freud, though the concept is not being used in the same way. We could quote here from Freud’s essay on the Uncanny, however, when he says “it is possible to recognize the dominance in the unconscious mind of a ‘compulsion to repeat’ proceeding from the instinctual impulses and probably inherent in the very nature of the instincts”. Perhaps Jennings’s experiment might be tapping into a deeper unconscious than even he is aware of. As

we have said before, the significance of Franklin Blake, in his disinhibited state, going into Rachel’s room in the middle of the night to take a precious jewel would not be lost on a Freudian.

In fact, while we can draw these kinds of comparisons in method between the doctor- detectives Jennings and Holmes, and the Casebook of Sigmund Freud, it is even more interesting to apply Freud’s theories to the material of the stories we are discussing. We can psychoanalyse the characters to our hearts’ content, wondering if both Sherlock Holmes and Ezra Jennings are sublimating the psychic pain of earlier traumas into their work (indeed, Jennings explicitly says that he is, and Holmes, while displaying no emotion himself, does offer the opinion that “Work is the best antidote to sorrow, my dear Watson” on the death of the latter’s wife). If we posit the idea of Freud’s Unconscious, we can then read the manifest material of these narratives for latent content linked to repressed traumas on the part of the authors, their characters, and the whole society in which they were writing.

Herbert Ross, The Seven Percent Solution, 1976, (Alan Arkin as Sigmund Freud and Nicol Williamson as Sherlock Holmes. Courtesy: Universal/ The Kobal Collection) https://www.frieze.com/article/dream-factory

We could even draw comparisons between the act of writing a detective fiction, and the reconstruction of the narrative of childhood trauma from dreams and symptoms expressed in an adult patient. When Ezra Jennings hands over his “analysis” of Mr Candy’s ramblings, with the gaps filled in, Franklin Blake expresses “admiration of the ingenuity which had woven this smooth and finished texture out of the ravelled skein”(388), he could be describing the piecing back together of the story of the crime from the hints that are left, or the work of the author of the detective narrative, in his backward construction of the investigation from the original idea of the crime.

It is not surprising that Freud’s development of psychoanalysis is contemporary with the rise of detective fiction. The methods of the detective and the psychoanalyst are interapplicable, with the detective diagnosing the mystery, and reconstructing the crime, as the analyst investigates the repressed trauma that has led to the clues exhibited in the patient’s neuroses and symptoms.

So we’ve looked at Ezra Jennings and Sherlock Holmes as drug addicts, scientists, doctors, magicians, logicians, psychoanalysts, and neurotics, and so I think perhaps it’s time to leave it there. Any questions?

JILL LIEBOWITZ

Jill grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area, where one in four people are self-described mental health professionals, and all the others either work in tech or are homeless. A teenage malcontent, she went into a Goth phase in the ‘90s that never really ended. She attended the University of California at Berkeley, where she studied Film and Creative Writing, and worked tirelessly as a social-justice campaigner. After a Junior Year Abroad spent down and out in Paris and London, she was accepted to an MFA programme at Columbia in Creative Non-Fiction. Her work has been awarded a number of prizes, and published in many journals and reviews. Her first collection of poetry, How Bright Things Are, was published in 2015. She is currently preparing a collection of essays and cultural criticism, to be released in 2022. Her hobbies include entomology, etymology, archaeology, burlesque, and radical feminist witchcraft.